Yesterday morning, we left Rome driving a rented Peugeot 3008, with the rising sun just touching the Colosseum and our minds set on the next stop: Genoa.

After a few hours behind the wheel and about €30 paid in tolls 😩, we stopped in Pisa, where the Leaning Tower seems to rise just to challenge its visitors.

Designed in 1173 by Bonanno Pisano as a simple bell tower for the cathedral, construction halted at the third level when the clay and sand foundation could no longer bear the weight. Nearly a century later, work resumed and the upper levels were built with a slight tilt to the north—an unintentional “correction” meant to counteract the shifting ground. In the 1930s, Mussolini launched a grand plan to straighten it, only to defy gravity in totalitarian style—and, surprisingly, worsen the lean. The restorations from 1990 to 2001 brought the angle back to about 4° and secured its stability for another three centuries, without diminishing its charm as a tourist magnet.

Although I’m not a fan of climbing narrow, tightening stairs as if the tower has a fear of space, I gathered my courage and headed up to the top with George. At first glance it seems like an extreme sport challenge, but in reality it’s milder than you’d expect. The only hurdles were the heat—easily rivaling a summer day on an unair-conditioned bus—and the crowd of tourists. Otherwise, the steps are friendly, and you can hold onto the walls without any problem. 😁

The Duomo next to the Leaning Tower has an imposing presence and, together with the tower, forms an architectural ensemble that blends medieval artistry with the traces left by nature and history in stone.

We lingered there for at least two hours. There’s so much to see, and we had so little time. Afterwards, we wandered on foot through the city. The surroundings were calm and peaceful—Pisa felt like a small provincial town in contrast to Rome’s hustle, with streets shaded by blooming trees and houses with well-kept gardens.

Once we’d ticked off that landmark, we set off for Genoa, aiming to arrive before 7 pm. We booked an apartment in the historic center, just a few minutes’ walk from the port and the city’s financial district.

Genoa is a city that reveals its charm gradually. It doesn’t flaunt its treasures ostentatiously but hides them carefully among narrow alleys, austere facades, and quiet corners of history. This very discretion makes it all the more fascinating.

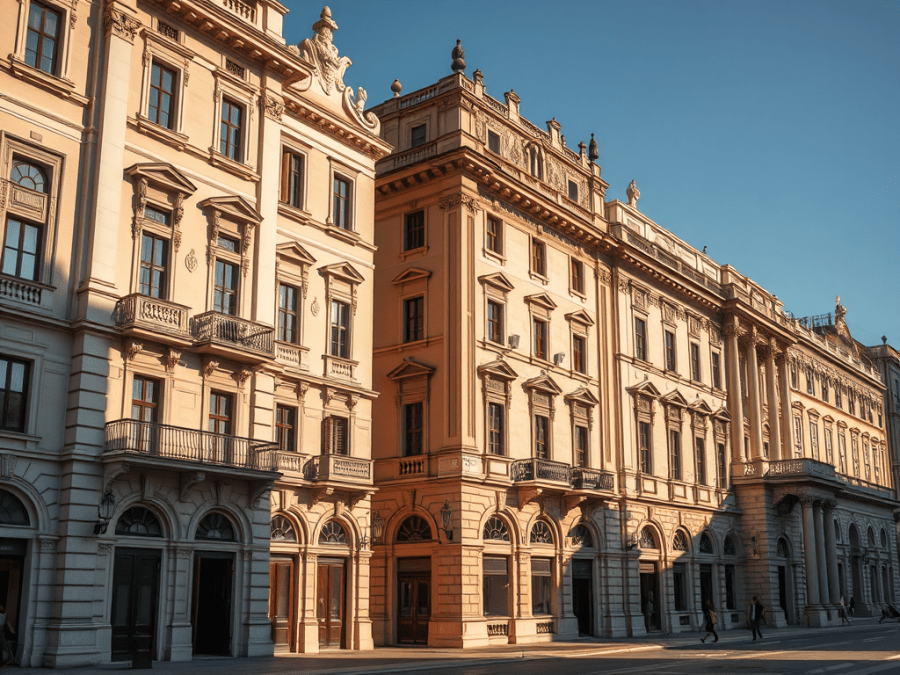

So here we are today on Via Garibaldi, formerly known as Strada Nuova, to visit the Palazzi dei Rolli—a group of palaces that, although less known than other Italian attractions, offer an exceptional cultural experience.

Diplomacy, Prestige, and Hospitality: The Story of the Rolli Palaces

In the past, Genoa was not only a prosperous city due to trade, but its entire identity was also shaped by it. Strategically located on the Ligurian coast, the Republic of Genoa became, in the 16th century, a major player in Europe’s commercial and financial networks. This rise attracted increasingly high-ranking visitors: ambassadors, cardinals, princes, and monarchs.

However, the city lacked an official residence to receive such guests with proper protocol, and the existing inns did not meet the standards required. In this context, the Senate of the Republic issued a decree in 1576 establishing a unique system in Europe: the Rolli degli alloggiamenti pubblici. The most sumptuous private residences of Genoese nobility were listed in an official register—the “rollo”—and selected by lottery to host distinguished visitors.

Over time, five such lists were issued. Among the notable guests were the Duke of Joyeuse (brother-in-law of King Henry III of France), Pietro de’ Medici (brother of the Grand Duke of Tuscany), and Queen Margaret of Habsburg (wife of King Philip III of Spain). Today, these palaces no longer host royalty, but they continue to impress with their elegance and refinement.

In 2006, the ensemble known as “Le Strade Nuove and the system of the Palazzi dei Rolli” was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The reasons are clear: remarkable architectural diversity, ingenious adaptation to the city’s topography, and the historical value of an unprecedented public hospitality system. The palaces reflect a sophisticated society where prestige, art, and civic responsibility were harmoniously intertwined.

Palazzo Rosso – A Journey Through History and Art

Our visit began with Palazzo Rosso, officially known as Palazzo Brignole Sale, a noble residence built between 1671 and 1677 by brothers Rodolfo and Gio Francesco Brignole Sale, members of one of Genoa’s most influential families. Architect Pietro Antonio Corradi designed the building in a sober yet elegant Baroque style, with a square inner courtyard and two wings connected by loggias inspired by the works of Bartolomeo Bianco.

The palace interior is a true gallery of painted symbols and myths. Between 1679 and 1694, masters such as Domenico Piola, Gregorio De Ferrari, and Paolo Gerolamo Piola decorated the rooms with allegorical frescoes inspired by Greco-Roman mythology and the moral philosophy of the time. Each room has a distinct theme: the seasons, human life, the liberal arts. In one hall, painter Gio Andrea Carlone illustrated the Allegory of human life as a symbolic journey between light and darkness, hope and transience—subtly capturing the fragility of the human condition. In another room, Paolo Gerolamo Piola rendered the myth of Diana and Endymion with dreamlike grace, transforming the legend into a scene suspended between reality and myth, where time seems to pause in contemplation.

The palace’s art collection is as impressive as its decor. Highlights include works by Van Dyck, Guido Reni, Veronese, Guercino, Dürer, Bernardo Strozzi, and Mattia Preti. The portraits of the Brignole Sale family, painted by Van Dyck, are not just artworks but visual testimonies of an era when prestige was expressed through refinement and artistic patronage.

In 1874, Maria Brignole Sale, Duchess of Galliera, donated the palace and its collections to the city of Genoa, with the express wish that they be preserved “for the glory of the city and the education of its citizens.” Today, after careful restorations, Palazzo Rosso is not just a museum but a living lesson in history, art, and memory.

From the rooftop terrace—open to visitors—the city unfolds in a sweeping panorama: medieval rooftops, Gothic towers, Baroque domes, and, in the distance, the shimmering Ligurian Sea. It’s a place where the past still seems to breathe—quietly, yet profoundly.

🎟️ Palazzo Rosso – Visitor Information

🕘 Opening Hours:

- Tuesday–Friday: 09:00–18:30

- Saturday–Sunday: 09:30–18:30

- Closed on Mondays

💰 Tickets:

- Single ticket: approx. €9

- Combined ticket (Palazzo Rosso + Bianco + Doria Tursi): €12

- Free admission for children under 18 and on the first Sunday of each month (check official website for conditions)

⭐ Highlights:

- Baroque frescoes by Domenico Piola and Gregorio De Ferrari

- Portraits by Van Dyck and works by Veronese, Reni, Guercino

- The “Allegory of Human Life” hall and the myth of Diana and Endymion

- Panoramic rooftop terrace with views over Genoa

Palazzo Bianco – Between Aristocratic Sobriety and Artistic Refinement

If Palazzo Rosso impresses with its Baroque exuberance and domestic atmosphere, Palazzo Bianco offers a different experience—more sober, yet no less fascinating. Built between 1530 and 1540 for Luca Grimaldi, a member of one of Genoa’s oldest noble families, the palace originally had a modest appearance, which is why even Rubens did not include it in his famous album dedicated to Genoese noble residences.

The building underwent a radical transformation in the 18th century, when it was acquired by Maria Durazzo Brignole-Sale, who commissioned a complete reconstruction in the late Baroque style. The façade was adorned with white stucco, giving the palace its current name—Palazzo Bianco. The interior was enriched with works by Taddeo Cantone and Antonio Maria Muttone, who added discreet elegance and architectural balance.

In 1884, Maria Brignole Sale De Ferrari, Duchess of Galliera, donated the palace to the city of Genoa, along with a valuable art collection and funds for its maintenance. Thus, Palazzo Bianco became the core of the city’s Municipal Museums and one of the most important art centers in Liguria.

The collection housed here is remarkable for its diversity and quality. Visitors can admire works by Caravaggio, Rubens, Van Dyck, Zurbarán, as well as Genoese painters such as Bernardo Strozzi, Valerio Castello, and Domenico Piola. One of the most famous paintings is Venus and Mars by Rubens—a composition full of dynamism and sensuality that contrasts with the sobriety of the architecture.

A lesser-known story tells that in the 19th century, the palace was rented by an art-loving marquis, Carlo Cambiaso, who opened his collection to the cultured public. It is said that every Sunday, the inner courtyard would fill with musicians, poets, and foreign travelers who came not only for the art but also for conversation and ideas. For a time, Palazzo Bianco became a cultural salon of the city.

Today, a visit to Palazzo Bianco is a journey through European art schools—from Flemish to Spanish painting, from the Renaissance to the Baroque. It is a place where aristocratic sobriety blends with aesthetic refinement, and each room offers a new perspective on the visual history of Europe.

🎟️ Palazzo Bianco – Visitor Information

🕘 Opening Hours:

- Tuesday–Friday: 09:00–19:00

- Saturday–Sunday: 10:00–19:30

- Closed on Mondays

💰 Tickets:

- Single ticket: approx. €9

- Combined ticket (Palazzo Bianco + Rosso + Doria Tursi): €12

- Free admission for visitors under 18 and on the first Sunday of each month (check the official website for current conditions)

⭐ Highlights:

- Masterpieces by Caravaggio, Rubens, Van Dyck, Zurbarán

- Genoese, Italian, Flemish, and Spanish painting from the 16th–18th centuries

- Sculptures, furniture, and decorative arts

- Late Baroque façade and 18th-century interior decorations

Palazzo Doria Tursi – Power, Prestige, and Architectural Harmony

The final palace on our itinerary—and certainly the most imposing—is Palazzo Doria Tursi, a residence that dominates Via Garibaldi not only through its size but also through its historical symbolism. Construction began in 1565 for Niccolò Grimaldi, an influential banker known as il Monarca due to his impressive number of noble titles and close ties to the Spanish court. It is the only palace on Strada Nuova built across three plots of land, allowing for a grand architectural layout.

Architects Domenico and Giovanni Ponzello, disciples of Galeazzo Alessi, designed a structure that combines Mannerist monumentality with an ingenious interior layout: a vast atrium, a monumental staircase, and a raised inner courtyard that creates a spectacular play of light and perspective. The façade—one of the longest on the street—is adorned with alternating bands of pink stone from Finale Ligure, black slate, and white Carrara marble, forming a rare and elegant chromatic composition. Above the windows, sculpted grotesques—masks with animal features—add a subtle theatrical touch.

In 1597, the palace was purchased by Giovanni Andrea Doria, who gifted it to his son Carlo, Duke of Tursi—hence the current name. Later, in 1820, it was acquired by Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia, and in 1848, it became the Genoa City Hall, a role it still fulfills today.

The palace interior reflects the height of Genoese refinement. The salons are decorated with frescoes, stuccoes, and period furniture, and some of the artworks on display come from the Palazzo Bianco collection. A special space is dedicated to the memory of Niccolò Paganini, the city’s most famous son. Here, his legendary violin, Il Cannone, crafted by Guarneri del Gesù, is on display—an instrument that has become a symbol of virtuosity and musical passion.

A local legend tells that Paganini, known for his enigmatic temperament, once refused to perform in the palace’s salons, claiming the acoustics were “too perfect” to express human suffering. It is said that on quiet nights, the sound of a violin can sometimes be heard from the room where the instrument is kept—a spectral echo of the genius who redefined 19th-century music.

A visit to Palazzo Doria Tursi is not just a journey through the history of a family or a city, but a complete experience of power expressed through architecture, art, and history. It is a place where Genoa asserts its identity with dignity and restraint, never ostentatious, but with a force that cannot be ignored.

🎟️ Palazzo Doria Tursi – Visitor Information

🕘 Opening Hours:

- Tuesday–Friday: 09:00–19:00

- Saturday–Sunday: 10:00–19:30

- Closed on Mondays

💰 Tickets:

- Single ticket: approx. €9

- Combined ticket (Palazzo Doria Tursi + Rosso + Bianco): €12

- Free admission for visitors under 18 and on the first Sunday of each month

⭐ Highlights:

- “Il Cannone” violin of Niccolò Paganini

- Mannerist architecture and a façade of marble, slate, and pink stone

- Furniture, tapestries, and decorative arts from the 17th–19th centuries

- Official salons and the suspended inner courtyard

Discover more from "The world is your oyster".

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.